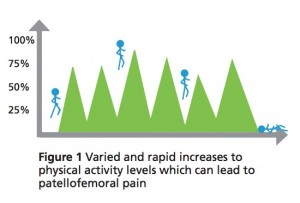

This is the second part of four in my series on Runner’s Knee. If you’re new here, be sure to start with Part 1: Load Management.

Last week, we gave you the first in our four part series of how best to manage Runner;s Knee. I hope you found the blog on load management interesting and informative.

This week, I want to discuss the most recommended treatment not just for runner’s knee, but for all musculoskeletal injury: exercise-based rehab.

I am going to declare my bias early: I am a passionate physiotherapist, exercise is a core skill of my profession and there is robust evidence that it is an effective tool in helping patients get better. However, it is no panacea and we must strive to do better with it and understand more about it.

We have high-quality evidence that exercise is effective in managing Runner’s Knee for both short and long term. However, it does not help everyone, and surely not all patients need the same program. So, what could we be doing better?

Firstly, let’s look at the evidence. What we know for sure is that we need to focus on more than just the quads. We now have two Level 1 pieces of evidence that suggest a mixed bag of hip- and knee-based exercises are the most efficient way to treat knee pain for some runners.

First, the good news: In both of these studies, participants pain went down and their function improved. The not so good news: Both of these studies used different exercise programs. So what should you do? Does it matter?

Picking the best exercises for runner’s knee

In my professional opinion, choosing the best exercises for Runner’s Knee for a given individual all comes down to specificity. Take this paper:

This paper looks at women with specific hip weaknesses, who were given a strength-based program. A specific intervention targeting a specific deficit led to a successful outcome. This should translate to specific exercise programs for specific patients. As my close friend and colleague Simon Lack says:

“We should not be prescribing exercises to our patients, we should be prescribing exercise to our patient”

I know this is difficult information to present in an article like this, offering general advice, but I’m going to try!

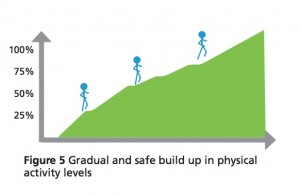

For the average runner, a program should start with a neuromuscular activation phase. This translates to low load, high sets and reps, regular (up to daily) completion and small, specific movements. This should allow for reasonably pain-free exercise, improvement in the “brain-body” connection and increased confidence for the patient.

The next phase to tackle would be what is known as strength endurance. As your symptoms improve, load should go up, sets and reps should reduce and completion should drop (up to 4-5 times per week). Running is an endurance activity. The progression in load will give our tissues the capacity to tolerate an impending return to running.

For some, that will be where the ceiling lies. However, if further progression were required, then a pure strength phase would come next. Further increases in load coupled with lower sets/reps and weekly completion.

Lastly, we would have power (moving loads at speed), but unless you are a sprint athlete, this is rarely required for rehabilitation purposes.

FREE DOWNLOAD: Runner’s Knee Rehab Resources [PDF]

Take home messages

- Exercise based rehab works – in some cases better than others.

- We (physios in general) could be doing better with how we prescribe corrective exercises.

- Think beyond the quads. When considering the best exercises for Runner’s Knee, make sure you work the glutes!

- Specificity is key – every case is unique!

As always, progress gradually, listen to your body and if in doubt, seek the advice of a professional!

The post Can You Cure Runner’s Knee? [Part 2] appeared first on Run Coaching, Ironman and Triathlon Specialists - Kinetic Revolution.

from Run Coaching, Ironman and Triathlon Specialists – Kinetic Revolution http://www.kinetic-revolution.com/best-exercises-for-runners-knee/